Cabinet committee set up on Devasthanam Board

Saturday, 27 November 2021 | PNS | Dehradun

The high powered committee has submitted its report on the issue.

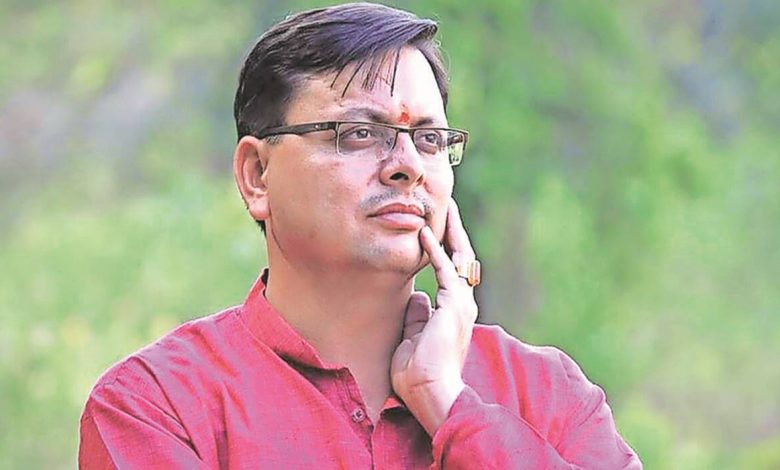

In what is being viewed as the BJP government’s plan of action to take back the contentious Char Dham Devasthanam Management Board, the chief minister Pushkar Singh Dhami has said that a cabinet subcommittee has been set up on the issue. Talking to the media persons on Saturday the CM said that the state government has received the final report of the high power committee set up on the issue. He said that a cabinet committee would study the report for two days and based on its recommendations the state government would take a decision on the Devasthanam board.

The Devasthanam board bill was tabled by the BJP government during the tenure of then chief minister Trivendra Singh Rawat during the winter session of Uttarakhand assembly in the year 2019. The Teerth Purohits and stakeholders of the char dhams are opposing the board vehemently. Immediately after assuming charge as CM Pushkar Singh Dhami had indicated his soft sand on the issue and had set up a high powered committee under the chairmanship of senior BJP leader Manohar Kant Dhyani on the issue. It is being speculated that the Dhami government could repeal the bill during the upcoming winter session of assembly.