Advani’s Jinnah flip- flop: Posturing or something more?

VIEW POINT

Romit Bagchi

Romit Bagchi

It was the time when a shell-shocked Bharatiya Janata Party was nursing its wounds in the aftermath of the 2004 poll debacle. Such was the shock that a section of its leaders was seriously pondering over the extent to which the party should toe the Hindutva agenda. These leaders, mostly the battle-hardened veterans who had weathered many a storm in their political careers, believed that the party should shed its pro-Hindu image because it cut both ways, hindering its further growth across India.

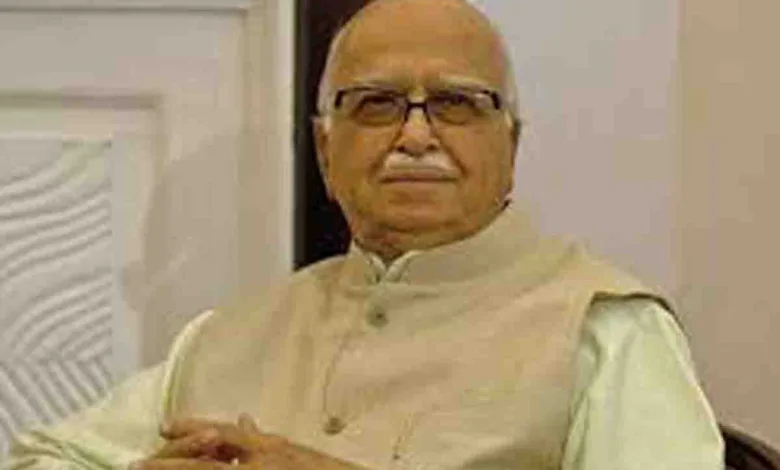

With intense churning going inside the party, Lal Krishna Advani, who had zealously helmed the Ram Mandir movement with full-throated patronage of the BJP’s ideological fountainhead Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, helping the party break out of the ideologically ambiguous and electorally unproductive mould, stunned all when he, during his four-day Pakistan visit in June 2005, lauded the principal architect of the country’s Partition and founding father of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah. What is more, he was the first important Indian leader to visit the mausoleum of Qaed- E- Azam and offer ‘chadar’ at his tomb. And what he wrote in the visitors’ book there is quite stupefying.

Now, let us go further back to the fateful days just preceding and following the Partition. The same Advani, then a youngster, was one of the 41 accused of the Jinnah assassination conspiracy case filed in a police station in Pakistan on September 10, 1947 after an explosion occurred in a house in Shikarpur Colony in Karachi where Advani along with some RSS volunteers was staying. As per the files related to this case, the accused were making bombs when one bomb went off, killing one person. Subsequently, the prosecution framed a conspiracy case for an attempt to assassinate Jinnah along with some other senior Muslim League leaders, including then Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan. During the probe, police claimed to have seized not just explosives but RSS documents from the house that allegedly revealed a plan to carry out terrorist activities throughout Pakistan. The special tribunal, constituted to try the case, pronounced its verdict a year later with two of the accused being awarded prison terms. However, the case against the absconders, including Advani, was transferred to a dormant file. Later, when Advani was the Union Home minister, Pakistan dug up the records of the Shikarpur conspiracy case and speculation abounded for a time that a tribunal might be constituted to try the absconding persons in absentia.

Advani, initiated as a swayamsevak when he was 14, became the secretary of the RSS’s Karachi branch. Just 10 days before the Partition, then RSS chief MS Golwalkar addressed the last and the largest ever Hindu congregation in the history of Karachi comprising over 10,000 uniformed RSS volunteers and Advani was the in-charge of the gathering. After the Partition, he migrated to truncated India in September 1947 along with other RSS volunteers of Karachi.

Now let us see what the BJP patriarch wrote in the visitors’ book of the mausoleum of Jinnah: “There are many people who leave an irreversible stamp on history. But there are few who actually create history. Qaed-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah was one such rare individual. In his early years, leading luminary of freedom struggle Sarojini Naidu described Jinnah as an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. His address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947 is really a classic and forceful espousal of a secular State in which every citizen would be free to follow his own religion. The State shall make no distinction between the citizens on the grounds of faith. My respectful homage to this great man.”

Though this laudatory remark about a leader whom the Sangh Parivar portrays as the ‘principal villain of the ancient land’s sinister division’ sparked strong consternation within the BJP, the RSS and the latter’s family of affiliated organisations, an unperturbed Advani justified his remark on Jinnah repeatedly.

Although the then Pakistan government, seemingly sceptical, refrained from responding to Advani’s outreach gesture, a popular daily of the country The News in its editorial wrote appreciatively : “His remarks have certainly given him a new look among the Pakistani people, who otherwise would reject him as a hardcore radical with nothing good to contribute to peace.”

Back in India, what was bound to happen did happen. With alarm bells ringing, the RSS brass decided to crack the whip. Advani offered to quit as the party president on June 7, 2005, but withdrew it four days later. Still wilting under pressure, the embattled patriarch finally stepped down as the party president on December 31, 2005 with a year left for the completion of his term.

Now, the question is: why did he visit Jinnah’s mausoleum and hail him as a great man despite knowing that these would not go down well with the Sangh ideologues?

Some said that he had already decided to quit as the party president before his trip to Pakistan because of the widening gulf between him and the Sangh. Some said that his Jinnah gesture was a desperate posturing to reposition himself politically by breaking away from his Hindutva hawk image trap and to recast himself in the mould of Vajpayee as the Prime Minister in waiting. Or maybe the quintessential Ayodhya warrior had evolved in the course of his storm-swept political career from rigidity to flexibility, from exclusivity to inclusivity, from subjectivity to objectivity-his subjective, prejudiced view of history giving way to a dispassionate, objective treatment of history.

Let us recall what Jadunath Sarkar, hailed as the father of modern historiography in India, said: “I would not care whether truth is pleasant or unpleasant and in consonance with or opposed to current views. I would not mind the least whether the truth is or is not a blow to the glory of my country. If necessary, I shall bear in patience the ridicule, the slander of friends and society for the sake of preaching truth. But still I shall seek truth, understand truth and accept truth.”

However, the RSS is not meant for objective historiography; it is meant to carry out relentlessly and unfalteringly its mandated task of organising and strengthening the Hindu community, taking all ridicule and slander in its stride. For it remains unshakably convinced that this-as contrasted with the chicanery of Muslim appeasement- is the only way for achieving the Hindu-Muslim unity on an enduring basis founded on the fulcrum of this ancient land’s civilisational ethos whose assimilative power is infinite.