Shyama Prasad’s fateful journey to Kashmir, defying permit mandate

VIEW POINT

Romit Bagchi

Romit Bagchi

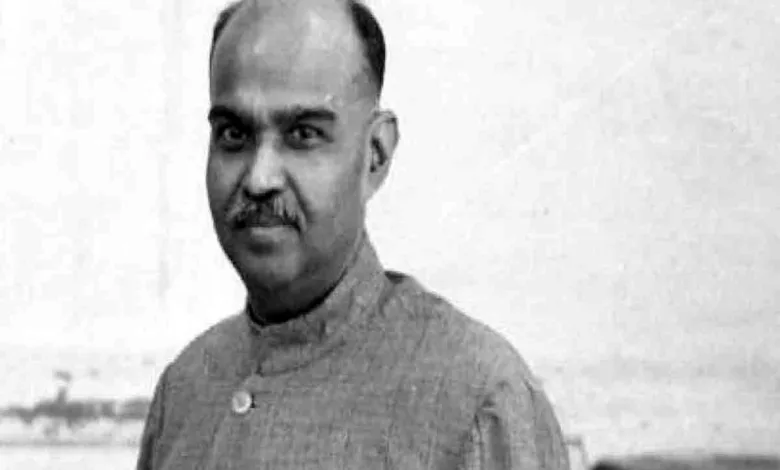

With the Supreme Court’s endorsement of the Narendra Modi government’s move to scrap the Article 370 of the Constitution that provided the erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir state a special status, things seem to have come full circle. Now, as the role of the founder of Bharatiya Jana Sangh-now Bharatiya Janata Party-Shyama Prasad Mookerjee is in focus again with many believing that he was martyred for the cause of integrating Kashmir with the rest of India, it is relevant to recall what happened in course of his momentous journey to Kashmir with the demand for withdrawing the special status of Jammu and Kashmir. Ignoring the premonition of many close to him that it portended ill to him, he set out for Jammu with a few companions.

Just before entraining for Jammu at Delhi railway station on May 8 1953, Mookerjee issued a statement explaining why he had decided to go to Jammu without applying for entry permit collecting which was required for a person from outside the state for visiting it. “Mr Nehru has repeatedly declared that the accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir to India has been hundred per cent complete. Yet it is strange to find that one cannot enter the State without a previous permit from the Government of India,” the statement, in part, read.

As his arrest seemed imminent, a noted vaidya Guru Datt was travelling with him to take care of him in case he was put under arrest. A young Jana Sangh activist from Dehradun Tek Chand aside from his secretary Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Bal Raj Madhok was also accompanying him.

With thousands of people coming to greet the leader at every station the train stopped, as he reached Ambala Cantonment, he sent a telegram to Sheikh Abdullah a copy of which was sent to Pandit Nehru, stating that he would like to see him if possible. He received Sheikh Abdullah’s reply the next day when he reached Phagwara wherein the Kashmir leader wrote that the timing of his visit was inappropriate and so it would not serve any useful purpose. Nehru did not reply.

While in Jalandhar, he addressed a media conference. Queried on the UNO’s stand on Kashmir, he said that India had taken the Kashmir issue to the UNO for stopping Pakistani aggression and not for settling how and when plebiscite was to be held there. In his inimitable sarcastic style, he took a snarky jab at Nehru, mocking him for not showing courage to protest against the deflection from the main issue.

When he entrained for Amritsar, the deputy commissioner of Gurdaspur who was sitting in the same compartment with him told him that the Punjab government would not allow him to reach Pathankot and he might be arrested if he decided to defy the government order. Unperturbed, Mookerjee carried on with his journey, daring the government to arrest him. He was given an emotional welcome in Amritsar and there he halted for the night. The next day he resumed his journey to Jammu. But he was not arrested in Pathankot as threatened earlier; instead, the DC Gurdaspur told him he could proceed without a permit as the government of India had changed its mind. The government’s surprise volte face intrigued Mookerjee.

Bal Raj Madhok wrote in Mookerjee’s biography ‘Portrait of a Martyr’: “Pathankot gave him a royal farewell. Thousands of people with folded hands stood on both sides of the bazaar through which his jeep passed. Just before his departure, a 90-year-old lady blessed him in Punjabi: ‘My son, do not return until you are victorious.’”

It was around 4 pm when Mookerjee reached Madhopur checkpost on the bridge of the river Ravi. Among those present to see him off was the DC Gurdaspur. But as his jeep reached the middle of the bridge, he found the road ahead of him blocked by a posse of Kashmir police. His jeep stopped. A police officer came forward and handed over to him an order signed by the chief secretary of the state dated May 10, prohibiting his entry into the state. Mookerjee read it and then asked in a surprised voice why that order had been issued when the government of India had allowed him to proceed. The police officer nonchalantly said he had been instructed to hand over the order to him. When Mookerjee said he would go to Jammu defying the order the cop showed him the order of arrest issued by the director general of the state’s police dated May 11. The order stated that Mookerjee had acted, had been acting and was about to act in a manner prejudicial to public safety and peace.

Still, his cast-iron resolve did not flicker. His face set firm with a grim determination, he got down from the jeep along with Vaidya Guru Datt and Tek Chand. Others who were accompanying him were asked to go back. It was then that he first realised something was ominously amiss in the government’s unexplained and inexplicable turnabout. Feeling that things were unfolding as part of a premeditated conspiracy, he scribbled a message and handed it over to his companions who were returning. It read: “I have entered Jammu and Kashmir though as a prisoner.”

When he reached Udhampur it was around 10 pm. He looked extremely exhausted by his bumpy journey in the jeep. He suggested he be allowed to spend the night there, but the officer who was escorting him refused and told him that the night was to be spent at Batote. They reached Batote around 2 pm and spent the night there. The next morning they were driven to Srinagar. When the jeep stopped at Central Jail it was 3 pm. From there they were escorted to a tiny cottage on the slope of a hill, converted into a sub-jail, near Nishat Bagh far away from Srinagar, where he was to spend the last 40 days of his life as a prisoner.

Meanwhile, the news of his arrest sparked protests across the country. Demonstrations were held and hartals were observed in several places, including Delhi. Madhok wrote: “This gave a new impetus and direction to the satyagraha. Satyagrahis began to proceed to Jammu without the entry permit. ‘Jammu Chalo’ became their slogan.”

Something interesting happened in the Parliament. On May 13, the senior Jana Sangh leader and Mookerjee’s close confidant Nirmal Chandra Chatterjee (father of the late CPI-M leader and former Lok Sabha Speaker Somnath Chatterjee) raised the matter in the Parliament and asked why he had been allowed to proceed to Jammu by the Government of India as per the information given by DC Gurdaspur. Nehru confounded all when he said that the DC had not met Mookerjee at all. Madhok wrote that a Hindi daily of Delhi while commenting on Nehru’s denial had written that Mookerjee would not be allowed to return and to lambast Nehru for this blatant lie.

One Comment